No Time for Despair

Lessons from André 3000, redveil & Toni Morrison

I’ve been trying to avoid despair and falling into a hole of my own inaction. Recently, I heard someone say oppressed people don’t have the “luxury of despair.” Constantly overpowered people who are under attack, who require something beyond comfort, have to fight for their living. They can’t help but say, “I am still alive.” An acknowledgment that they continue on, that something kept them here even when it didn’t seem likely. Recognizing we need that declaration so we can avoid the pit ourselves.

Earlier this week, for the first time in more than 17 years, André 3000 released an album of new music titled New Blue Sun. Most surprisingly, it’s not anything close to the rap record fans like myself spent years begging him for. André, who, over the years, has been spotted playing and walking around with a flute, went a different direction. The lyricist committed himself to an entire album centered on woodwind instruments.

While André didn’t love the gamification of what those encounters became, NPR journalist Rodney Carmichael lent a different perspective: “You talked about the random André sightings and how it became like a game of Where's Waldo? But the thing to me that's interesting about those sightings is they started happening at a time when we weren't seeing or hearing much from you. And when we would see you, you would look at peace.”

Carmichael continued, “You were playing this flute and it was reassuring that whatever was going on with you, you seemed like you were in a good place. And with artists that we care about, when we're not hearing output from them, that's always a question. Are they in a good place?”

The music on New Blue Sun isn’t going to be something everyone enjoys. I’m still getting familiar with it myself. But it’s André declaring, “I'm happy. I'm happy when I'm playing. I'm exploring when I'm playing. I'm thinking when I'm playing.” As a fan, that has felt good to see. My classmate got me OutKast’s Speakerboxxx/The Love Below for my birthday in third grade, and I’m glad we’re still on this journey together.

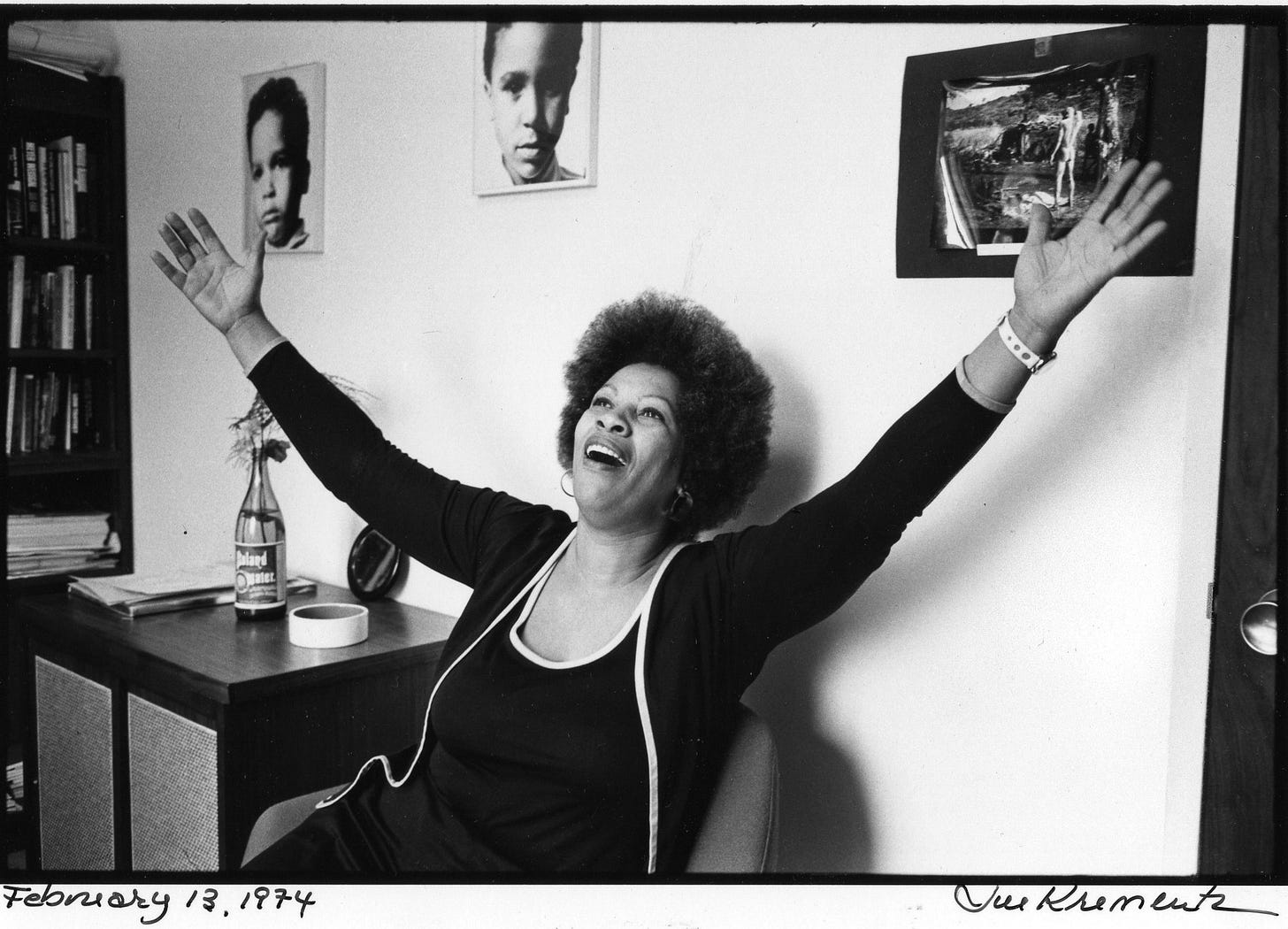

Despair is isolating; it leaves you feeling helpless. On a phone call the day after George W. Bush’s presidential re-election, writer Toni Morrison replied, “Not well,” to a friend asking how she was doing. Morrison continued, “Not only am I depressed, I can’t seem to work, to write; it’s as though I am paralyzed, unable to write anything more in the novel I’ve begun.” As Morrison continued to speak, her friend interrupted: “No! No, no, no! This is precisely the time when artists go to work—not when everything is fine, but in times of dread. That’s our job!”

After the call, Morrison began to think about as she described “artists who had done their work in gulags, prison cells, hospital beds; who did their work while hounded, exiled, reviled, pilloried… those who were executed.” When we step outside of ourselves and even look back, we see a precedent for staying the course, for choosing solidarity when self-pity calls incessantly. André 3000 said, “You’re only as good as the people that were before you.”

At the start of 2023, Pitchfork reporter Dylan Green interviewed 18-year-old rapper-producer redveil. The first time I heard veil’s hit song “pg baby,” I knew I loved it. But I didn’t realize he was referring to Prince George’s County, Maryland, an area where my mom used to teach. I also learned redveil is part Jamaican like me.

In the interview, Green breaks down redveil’s influences:

“veil’s parents, a Canadian-Jamaican mother and a father from New Orleans by way of the Caribbean island of Saint Kitts, separated when he was young, and he spent his youth traveling between their homes in PG County. Mom streamed gospel stations on Pandora; dad played classic R&B and hip-hop; veil’s older brother listened to underground rap and go-go music. By the time veil turned 10, he was playing his brother’s drum kit, which led to a short stint in a church band with his cousins. A year later, encounters with albums by Tyler, the Creator, J. Cole, and Logic inspired him to write songs of his own.”

This foundation impacted how redveil navigated underground rap. With a few albums along the way, it also led redveil to his best work yet: learn 2 swim, a record focused on staying afloat. When Green asked how the album came together, veil replied, “I feel like people that came before us in the previous generation of underground hip-hop, they’ve already established these styles. They’ve already done it and they’ve done it well. That’s not my job to do that; it’s my job to do whatever the next thing is, to evolve.”

At this year’s Camp Flog Gnaw, a music festival by Tyler, the Creator, redveil took the stage wearing a keffiyeh. At the end of his set, redveil talked to the audience while names of children recently killed in Gaza scrolled on the screen behind him. “Nobody on this fuckin’ list made it to the age of four,” he said. “Not one.” redveil made the boldest statement he could, covering the screen with the URL for Ceasefire Today before leading the crowd in chanting, “Free Palestine.”

Inspired by those who came before him, with an opportunity to perform at a festival for one of the artists who inspired him to make music, redveil made his voice heard. “You’re only as good as the people that were before you.”

Recently, I’ve been talking with Grandma T about where her family is from. It has helped me better understand my history and form tighter bonds to those in my life with similar lineages. Every reply I get from my grandma is a reminder she’s still here, there’s still more to learn, and everything she shares with me is something I can pass along to others.

It’s difficult for despair to get comfortable in rooms with others, especially those who dare to create and imagine. In André 3000’s NPR interview, Rodney Carmichael made a connection between the group of artists that André 3000 made New Blue Sun with, including Carlos Niño, Nate Mercero, and Surya Botofasina, to his start with the Dungeon Family—the Atlanta music collective which gave way to OutKast and Goodie Mob.

André felt this connection, too. “The last song on the album, it mentions the Dungeon. And that's on purpose.” He continued, “In the same way, when you talk about Carlos… and Nate… and Surya… and this whole community of players, it gives you an opportunity and support system to be as free as you can be.”

When I haven’t known what to do or say or what “enough” even looks like, I’ve turned to my people amid overwhelming horrors. They’ve welcomed my hurt and joined their sorrows with mine. This openness feels like freedom at a time when so many fight for it with all they have.

I’ve written about this many times before, but the siblings I write with—my homies J.T., Koku, Cole, and Kayla—make me feel like I can say what needs to be said. Kiese Laymon told Tamara K. Nopper, “Work with folks who can help you go beyond your vision. That’s what a dope collaborator does. They help you be bolder and more evocative.”

Watching redveil on stage, I felt inspired. For ESPN, author Danté Stewart wrote, “It's young Black people who embody the beauty of life; it's always been the young Black people.” I saw that beauty in redveil, which shows there’s more to hip-hop than what we’ve been handed.

I’ve seen a blueprint for aging thoughtfully in André 3000 and Toni Morrison, two artists whose pursuits of love made room for them to continue learning and evolving. “I think as an artist, you kind of got to put yourself out there to be prepared to respond,” said André.

“I'm a responding person. That's what I am. I'm responding to what's given to me. It's responding to my contemporaries. It's responding to what I love. It's responding to what I don't like. It's responding to all of that.” André went on to advise younger artists to explore and keep pushing. “Whatever you pay attention to, pay attention to what you're paying attention to and go for it.”

Toni Morrison repeated the words of her friend: “This is precisely the time when artists go to work. There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear.” Morrison continued, “We speak, we write, we do language. That is how civilizations heal.”

This world’s interconnected systems of violence are hell-bent on taking everything from us, which is why we can’t allow despair to imprison us in silence.

“We don't have to quiet our voice or our vibe or our confidence or our joy,” said Stewart. “We don't have to accept their definitions or their punishment. We know that to be us and to be free is to help others be them and be free.”

I’ve been trying to avoid despair, and my people have met me there. My co-laborers in hope. My reminders that we’re still here, which is to say we’re capable of fighting for another world—not resting on what we’ve done in the past but marching toward a more beautiful future.

Thank you!

I appreciate you reading! If you enjoyed, please share it with someone special.

Was this forwarded to you? Sign up here to receive my next newsletter directly in your inbox.

Support the newsletter: If you’d like to support my work, consider becoming a Paid subscriber to Feels Like Home or simply buying me a coffee.

Stay connected: For more content and updates, visit my website or follow me on Instagram, Threads, and LinkedIn.