Perfectly at Peace

A Black Kid's Ode to Kid Cudi

Hi! I wanted to give everyone something “new” to read this week while I work on another essay, so I revised one of my favorite pieces I published on Medium in 2022 and added a voiceover you can listen to while reading. For folks who are new to my work, Kid Cudi reposted this essay on Twitter and made my entire life:

With Kid Cudi recently celebrating 15 years since he released his debut album, Man on the Moon: The End of Day, it felt like the right time to resurface this essay. I hope you enjoy and share it with someone special. Scroll to keep reading.

“Happy to see how far I’ve come

To the same place it began

My dreams and imagination

Perfectly at peace

So I move along a bit higher”

– “Up Up & Away” by Kid Cudi

In July 2016, I pulled up to the Divide Music Festival in Winter Park, Colorado. I woke up early to drive a little over an hour from Denver with minimal caffeine—only a promise that I’d get to see one of my heroes perform that night: Scott Mescudi, the Cleveland, Ohio native, most notably known as Kid Cudi.

I didn’t pay much attention to the previous two albums Kid Cudi released before the festival: Speedin’ Bullet 2 Heaven (2015) & SATELLITE FLIGHT: The journey to Mother Moon (2014). Cudi has said he wanted all of us his albums to have a different sound. With these records, he seemed to have taken a significant departure from his first two Man On The Moon projects & his 2013 album Indicud.

I didn’t like Cudi’s debut album when I first heard it. Months passed before I decided to give it another try, and then more months passed before I could bring myself to listen to anything else.

The first chapter in Cudi’s Man On The Moon trilogy is brilliant. From the intro track, you find yourself in another world. With narration from hip-hop legend Common woven throughout the album, Cudi introduces you to his paranoia, as well as his unrelenting commitment to himself.

Even beyond Cudi’s debut album, I loved that he listened to the same music my white friends in high school introduced me to—especially with songs like “Pursuit of Happiness (Nightmare)” featuring MGMT & Ratatat, “Cudderisback” where he freestyles over a loop of Vampire Weekend’s “Ottoman,” and “The Prayer” off his 2008 mixtape, A Kid Named Cudi, where he flips “The Funeral” by Band of Horses.

As one of the only Black kids at my mostly white high school, I was isolated enough to think people who looked like me hadn’t heard of MGMT or Vampire Weekend. When artists like Chiddy Bang sampled MGMT’s “Kids” on “Opposite of Adults” or RZA and Lil Jon showed up in the music video for Vampire Weekend’s “Giving Up The Gun,” I saw how alternative rock and hip hop influence each other, as well as how Black people are more expansive than I was led to believe.

When Cudi headlined Divide Music Festival with Passion Pit, The Fray, Bleachers, and Edward Sharpe & The Magnetic Zeros, I was hardly surprised. More than anything, I was shocked he was close enough to my new home of Colorado Springs that I could drive to go see him.

Moving to a new city—a mostly white city—halfway across the United States from my people, I spent a lot of time wandering. This was especially true at Divide, a music festival nowhere near the size of Coachella or Lollapalooza, but nonetheless my first-ever music festival. Everything feels new when you’re in a new place. A mostly white place. That is, until Cudi arrived.

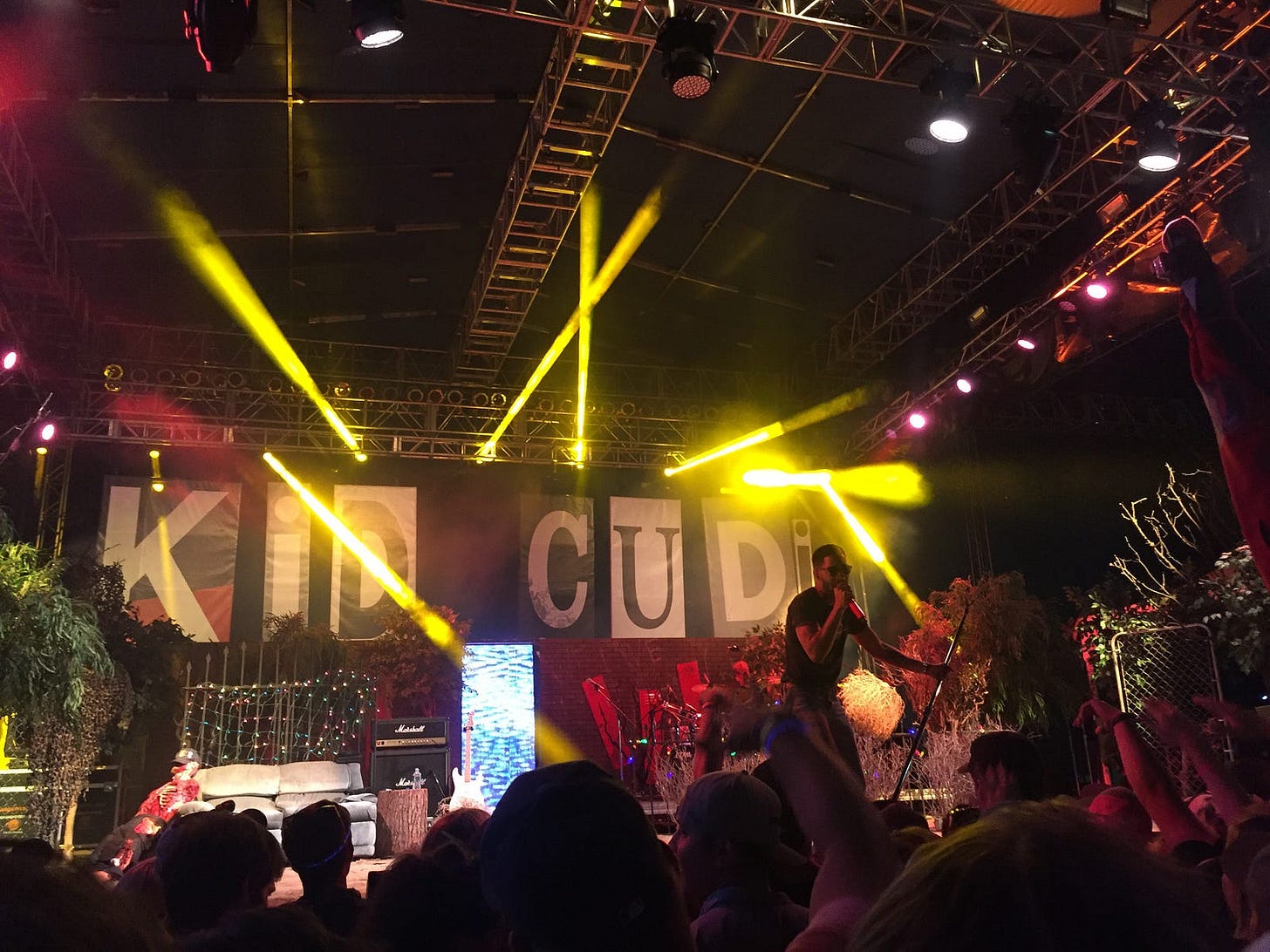

Cold War Kids and Passion Pit kept the main stage warm for Cudi, but eventually he let it get cold. Over an hour passed while a production crew moved an excessive amount of props onto the stage—a couch, some weird-ass skeleton in a hat, a chain-link fence, and a nursery’s worth of trees and decorative sticks. None of this should surprise fans of Kid Cudi, a musician so engrossed in his artistic vision that sometimes the listener’s convenience becomes secondary.

When the lights went dark and Cudi finally appeared on stage in shades and skinny jeans, it no longer felt like I was alone at this festival in the mountains. Cudi’s music and signature smile felt so familiar. I look back at my Snapchat Memories from that night—and surrounded by strangers, I can hear my voice among theirs belting out the hooks from “Soundtrack 2 My Life,” “REVOFEV,” “Up Up & Away,” and “GHOST!”

In the nine-second video clip I recorded of Cudi performing one of my all-time favorite songs, “GHOST!”, the video stops right before he finishes the opening lines of his first verse:

“Gotta get it through my thick head

I was so close to being dead”

In Kid Cudi’s music, he has never shied away from being open about the darkness that haunts him, how death sometimes feels awfully close. Even on his first-ever single, “Day ’N’ Nite,” a song he wrote after not being able to find resolution with his uncle who died, Cudi raps about attempting to escape from the pain:

“I try to run, but see, I’m not that fast

I think I’m first but surely finish last, last”

One of the reasons I fell in love with Cudi’s music is his willingness to be vulnerable about the hurt in his life. And still, he smiled. Still, he danced in front of hundreds of multi-colored balloons in the “Make Her Say” music video. And it felt like that smile shined brighter because of the secrets he wasn’t afraid to share.

It’s why, even with a heavy heart, I smiled two months after the Divide Music Festival when Cudi wrote on Facebook that he had checked himself into rehab for depression and suicidal urges, inspiring a string of conversations around race, mental health, and masculinity under the Twitter hashtag #YouGoodMan.

“It’s been difficult for me to find the words to what I’m about to share with you because I feel ashamed,” wrote Cudi. “Ashamed to be a leader and hero to so many while admitting I’ve been living a lie.” He added, “My anxiety and depression have ruled my life for as long as I can remember and I never leave the house because of it.”

Deeply moved by Cudi’s letter, I contributed to the #YouGoodMan conversation with a tweet remarking how important it was. I noted, “As Black men, we so often avoid vulnerability in order to protect ourselves from surrounding social realities.”

Kid Cudi is one of the artists who gave young Black kids like myself permission to feel and be open about what we’re feeling, even if that openness felt like something that could only be shared between a pen and paper. When I was in high school and fell in love with writing music and sharing it with my peers, I literally wanted to be Cudi. The way I wrote, the beats I wanted to rap on, it was all Cudi.

When I first heard “Cudderisback,” I knew I had to write to that beat, but I couldn’t find the instrumental. So, I opened Audacity’s free recording software and cut a section of Vampire Weekend’s “Ottoman” without the vocals. Then, I copied-and-pasted that part of the song until I completely remade the beat. When I finished, I rapped over it and gave my best Kid Cudi impression.

We’re often taught to think about our heroes as never faltering, but Kid Cudi is special because he was broken enough to let the light shine through. And he always wanted to shine for his people, considering his fans among them.

Closing his Facebook letter, Cudi wrote:

“Love and light to everyone who has love for me and I am sorry if I let anyone down. I really am sorry. [I’ll] be back, stronger, better. Reborn.”

Kid Cudi released his next album, Passion, Pain & Demon Slayin’, a month after he checked out of rehab. Because most of the songs were written prior to him checking himself in, we knew he had more to say.

In 2018, Cudi followed through on his promise to us and himself when he partnered with longtime collaborator and on-and-off friend Kanye West to release a seven-song album, KIDS SEE GHOSTS, where he provided us with a progress report on the standout track “Reborn.”

In recent years, Cudi’s hums have become their own entity—something that collaborators have had him sprinkle on their tracks like parsley to spruce up the presentation. Think “through the late night” by Travis Scott. They’re also a wave that artists like Phoebe Bridgers have wanted to ride, knowing how sweet the swell is. In a now-deleted tweet, Bridgers messaged Cudi, “Hum with me.” It was an invitation ahead of their 2020 duet “Lovin’ Me” where he does, indeed, hum with her.

We’re immediately taken somewhere familiar, somewhere that feels like home, when Cudi begins humming nine seconds into “Reborn.” Then, he jumps into the chorus:

“I’m so — I’m so reborn, I’m movin’ forward

Keep movin’ forward, keep movin’ forward

Ain’t no stress on me Lord, I’m movin’ forward

Keep movin’ forward, keep movin’ forward”

When Cudi recites these words, I swear I can hear him smiling. They feel like freedom. Not that he’s complete, but that he’s still going. It also feels like a mantra, like he’s trying to internalize this call to keep going through repetition. The more he says it, the more it’ll become true for him.

I relate with this as someone who regularly feels burdened by the world’s bleakness but so badly wants to believe another world is possible.

The phrase “Hope is a discipline” is often credited to abolitionist organizer Mariame Kaba. In an interview with The Intercept, she described the expression as being “more about the practice of making a decision every day, that you’re still gonna put one foot in front of the other, that you’re still going to get up in the morning. And you’re still going to struggle.”

I often forget Kanye West is on “Reborn,” which is easy to do because he only has one verse on the song. But it also feels intentional. This is Cudi’s song, Cudi’s story, Cudi’s promise.

In the second verse, Cudi points us back to his Facebook letter. “I am not at peace,” he wrote. “I haven’t been since you’ve known me.” Later, he added, “I deserve to have peace.”

On the song, Cudi raps in a conversational tone:

“I had my issues, ain’t that much I could do

Peace is somethin’ that starts with me (with me)”

Alcoholics Anonymous is a recovery group that is well-known for its twelve-step program. The first step reads, “We admitted we were powerless.” Cudi came to a similar place : “… ain’t that much I could do.”

As I’ve gotten older, peace isn’t optional for me; it’s a requirement. I need time and space to be, to let my mind rest.

“There’s a ragin violent storm inside of my heart at all times,” shared Cudi in his Facebook letter. “[I don’t know] what peace feels like. [I don’t know] how to relax.”

Because of these words, it feels like an exhale when Cudi begins the second verse on “Reborn”:

"Had so much on my mind, I didn’t know where to go

I’ve come a long way from them hauntin’ me

Had me feelin’ oh so low

Ain’t no stoppin’ you, no way

Oh, things ain’t like before

Ain’t no stoppin’ you, no way

No stress yes, I’m so blessed and”

When Kid Cudi sat down with Zane Lowe a few years later to talk about the third installment of his Man On The Moon trilogy, Man On The Moon III: The Chosen, that’s what it felt like: no stress.

As soon as you press play on the video, it feels like Cudi’s smile takes over the screen. A smile that immediately makes you smile, one that can’t help but bring you happiness and joy.

When author and poet Hanif Abdurraqib interviewed Kid Cudi for Billboard after the release of KIDS SEE GHOSTS, Abdurraqib wrote:

“Scott Mescudi grins like a person who knows that his next smile isn’t promised. His often arched eyebrows slowly dissolve, and the corners of his mouth extend to the edges of his face as if there is a new freedom waiting to be discovered there. At that point, Kid Cudi, as he’s better known, is mostly teeth. Once that smile arrives, it lingers. Cudi’s smile fights to exist, and it fights to stay.”

In 2021, I tweeted, “I’m thankful for every opportunity we get to see Kid Cudi smile.” And it’s true. With everything Kid Cudi has been through, I’m grateful we’ve been able to have him with us for as long as we have. That he’s still with us. That his daughter Vada, who has started writing her own songs, gets to see him grow older.

“Has the fight gotten easier, or have you found enough joy to eclipse the idea that you’re fighting at all?” asked Abdurraqib. And with that contagious smile I can already picture on his face, Cudi replied, “I have so much joy that I don’t feel like I’m fighting anymore.”

Music festivals can often be chaotic. But that night at Divide, there was a calm that covered the crowd. This was before Kid Cudi had written his letter telling us how unwell he was. And even with the jumping up and down and cheering, it felt like we were okay, that we had each other.

A contract between us and Cudi that we’d keep moving forward. Even if we didn’t know which way to go.

Thank you!

I appreciate you reading! If you enjoyed, please share it with someone special.

Was this forwarded to you? Sign up here to receive my next newsletter directly in your inbox.

Support the newsletter: If you’d like to support my work, consider becoming a Paid subscriber to Feels Like Home or simply buying me a coffee.

Stay connected: For more content and updates, visit my website or follow me on Instagram, Threads, and LinkedIn.

I feel all of this bro:

"Kid Cudi is one of the artists who gave young Black kids like myself permission to feel and be open about what we’re feeling, even if that openness felt like something that could only be shared between a pen and paper."

Ahhh I love this so much. I've been a Kid Cudi fan forever and this article makes me feel seen in my adoration and the reasons why. I also always loved that he was born and raised in Ohio (Cleveland).