There is No Face of the NBA

Reframing the debate for a new generation

Anthony Edwards says he doesn’t want to be the face of the NBA. “That’s what they got [Victor Wembanyama] for.” Rachel Nicols says the faces of the NBA are two players, LeBron James and Steph Curry, who are closer to retirement than they are to their next ring. “Your grandmother knows who they are.” ock sportello, one of my favorite NBA writers and evaluators of culture, says the league is in a “crisis of cool.”

Considering the discourse, thoughts race through my head about live-action Lilo & Stitch, the breath of fresh air that was Sinners, and if it’s true that lightning never strikes the same place twice.

I’m not arguing for the reclamation of a “better time” or forcing our current era to be something it’s not; I simply want to identify where we are and what we’re contending with. We don’t get to this place where we’re without a clear distinction of who the face of the NBA is apart from the broader cultural trends the league is steeped in and inevitably shaped by.

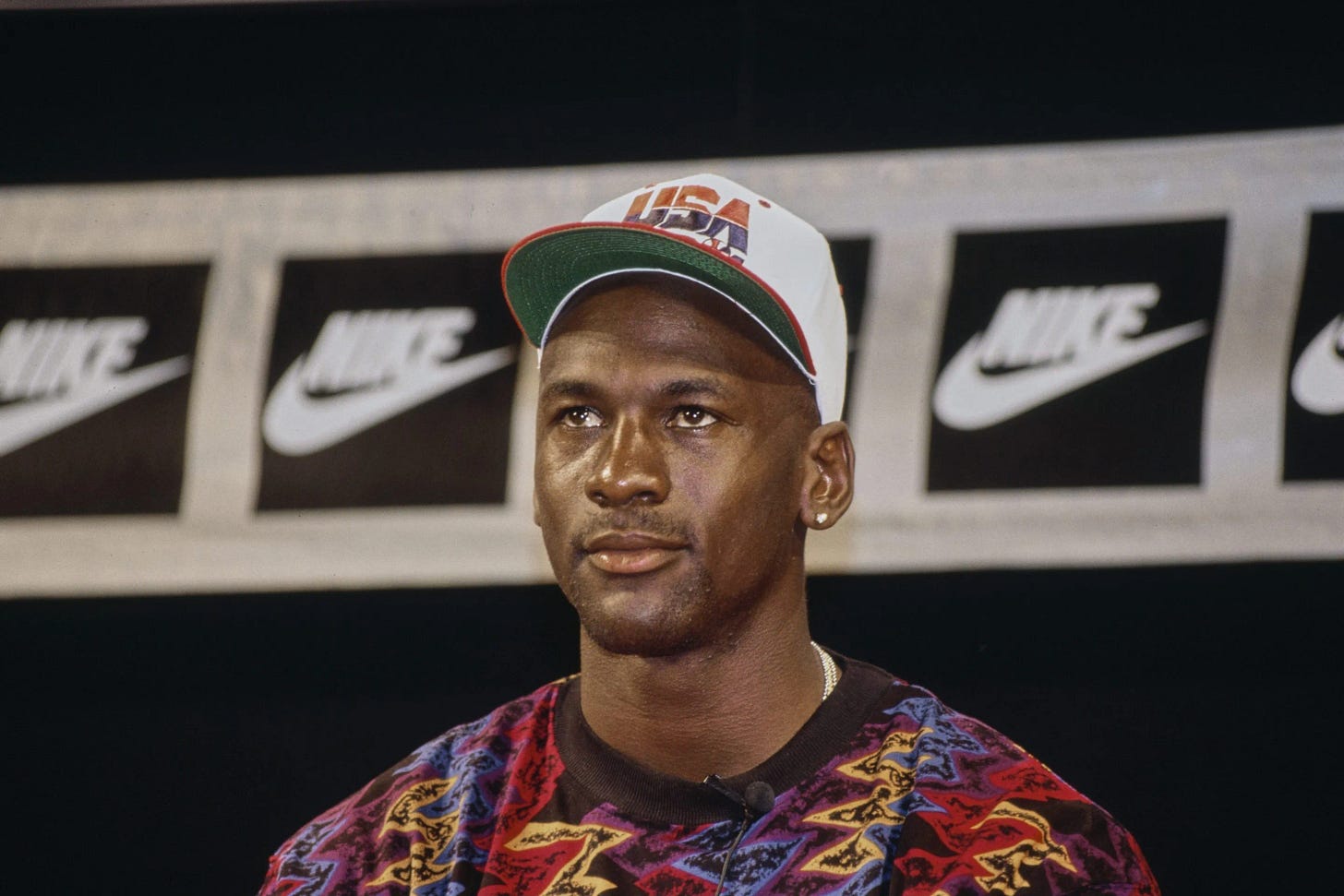

The face of the NBA is a media construct disseminated to fans as a means of engagement farming and rage bait, which is also evident in the Michael Jordan vs. LeBron James debate. These topics fuel impassioned arguments in barbershops, at lunch tables and, most importantly, on social media.

Our investment in these discussions tells the producers on ESPN and Fox Sports that this is something we care about. It’s our contribution to the machine. And it seems the further we get from the origin point, the more we lose the plot. Although the truth is, the plot was likely lost long ago.

The NBA as serialized melodrama—or reality TV as I wrote in a previous essay—isn’t new. The on-court competition and storylines created in and around the game attract viewers and allow the league to have a presence in fans’ lives even beyond tip-off.

As for the face of the league, capitalism necessitates marketability—the function of a business or organization to influence buy-in or sell itself to the masses. The NBA’s main commodity is its players, and the most public ones embody the story the league believes will best impact its bottom line.

In the Netflix documentary Untold: Shooting Guards, former player Gilbert Arenas explained, “To be a star in the NBA, you have to be an image that people will buy.”

“You’re not a regular-ass person,” declared Arenas. “You are a business.”

The NBA, as Sportello described, is in the “business of selling cool.” Ock added, “All professional sports leagues exist to sell advertisements, but the NBA is itself a sort of advertisement for its aesthetics, personalities, and sneakers—if there’s an NBA deep state, the Nike headquarters is where they conspire.”

Just as Nike uses players to sell its shoes, the NBA hand-selects players to represent its offerings globally. For example, the NBA kicked off this season with a commercial featuring several superstars, mostly from the Western Conference, including Anthony Edwards, Kawhi Leonard, Luka Dončić, Victor Wembanyama, and the outmatched Eastern Conference players Bam Adebayo and Jayson Tatum.

Noticeably absent from the ad are the NBA’s best-known players who led Team USA to an Olympic gold over the summer: LeBron James, Steph Curry, and Kevin Durant. It’s a thinly veiled (and smart) attempt by the league to lessen its dependence on the titans who have helped market the NBA even before their professional careers—all of which have been in motion for more than 15 seasons with LeBron having just completed his 22nd year.

This current iteration of the “face of the NBA” debate is fueled by the recognition that James, Curry, and Durant are finishing their tenures as the league’s Chief Marketing Officers. Here begins the hiring process and market testing for a new player or players to fill this role.

Leading candidates, including Tatum, Shai Gilgeous-Alexander, and Nikola Jokic, have won championships in the past couple seasons or are competing for one this season. These players were also featured in the official promo for this year’s NBA playoffs.

While the NBA is more talented than it’s ever been, Sportello argues that it’s also less cool than it’s ever been. This isn’t just about a decline in TV ratings. Ock theorizes that “the last decade of unsustainable, genetically-modified aura farming in the NBA has depleted the topsoil and established the preconditions for a swag dust bowl.”

In other words, players are losing their potency. Growing up, I developed a childhood obsession with Allen Iverson. A.I., as opposed to the artificial intelligence we’re now force-fed at every turn, was one-of-one. He felt real in the way theologians argue the authenticity of the Bible. Unconcerned with the merits of professionalism, Iverson expressed himself in ways that someone who cared about how they were perceived might think twice about.

It’s this imperfection and unapologetic commitment to himself that made Iverson the NBA’s most influential player. I wasn’t the only one who wanted to be like him; there was a long tail of rappers, as well as players who followed in his footsteps like LeBron, Carmelo Anthony, and even Gilgeous-Alexander. Shai is often seen sporting cornrows and a headband like A.I. did. But Iverson wanted to be like Mike.

In celebration of Michael Jordan’s birthday this past February, A.I. posted on Instagram, “The reason why the world knows Allen Iverson is because you gave me the vision.” He continued, “I always wanted to be like you!”

While fans can now see Iverson online from time to time, he and Jordan cemented their legacies and alchemized their auras before social media. They felt untouchable in a way that James, Curry, and Durant don’t—primarily because they didn’t feel like they were one degree of separation away. That sliver of separation being direct messages and comment sections.

We didn’t see A.I. howling about Taco Tuesday, nor did we get confirmation MJ heard the TikTok songs people made about him. Our window into these athletes’ lives was the press conferences we saw, commercials they were in, and headlines we read about them. There wasn’t an added layer of online persona. However, in today’s media landscape, walls are meant to be broken down, providing fans access—or at least the illusion of access—to their favorite players.

Mystique is a thing of the past. You can mention Kevin Durant in a tweet, and there’s a chance he’ll reply. Scrolling online, you’re likely to see your favorite player hosting a podcast, sharing what’s in their bag, or showing off their outfit in the team tunnel before a game. Whereas The Last Dance was the most we’d ever seen of MJ’s life and career, a quick sweep of Josh Hart’s X account will leave you with tweets like, “Have yall ever tasted yall significant others breast milk? Asking for a friend.”

Social media and always-on entertainment have also helped usher in the increase of micro-cultures—smaller, niche communities focused on specific topics and interests. Each of these groups have their own “face.” For example, there’s a whole universe of “Muse” accounts on X (formerly known as Twitter) dedicated to even the most obscure bench players.

“Fan accounts on NBA Twitter are nothing new, but these Muse accounts are a different breed,” wrote Jared Ebanks for SLAM. “Using StatMuse’s AI-powered sports statistic search engine, accounts fuel online discourse, banter and engagement plastered with cartoonish illustrations of players across the [league]. Any statistical feat that you could ever dream of gets posted on a nightly basis.”

These hyper-personalized expressions of fandom—the Daylist-ification of the NBA—have created an environment where it’s virtually impossible to have one “face” of the league because we’re bombarded with so many faces. While the NBA and its media partners may serve up a select few players, social media puts the whole league at our fingertips. We create our own stars while league-approved personalities are prone to becoming “foul merchants” and “overrated.”

As evidenced by the NBA’s brand positioning throughout this season, the league is keen to create the same magic it found with LeBron, Steph, and KD, which becomes more challenging with every passing generation. The culture in which MJ, Magic Johnson, and Larry Bird defined the game is different than the era that followed—and players like A.I., Kobe Bryant, and Shaquille O’Neal did their best to rise to the occasion.

As today’s culture has become a nostalgia feedback loop reaching back into the archives of past generations, attempts have been made to recapture the energy of those eras. But as we’ve learned from our daily trips to the office printer, copies lose their quality.

Circling back to my thoughts on movies and TV, I’ve been bummed by how Disney is trying to capture a new audience with live-action Lilo & Stitch while pulling in fans that grew up with the franchise. It may be smart from a business perspective, but it cheapens the product as the remake will never match the emotional connection people have to the original.

The Real Housewives of New York City is another instance where the original franchise—due to a multitude of reasons, including when it was filmed, how new reality TV still felt, and the cast itself—tapped into something that its reboot was unable to. Many still cite the original RHONY as the golden years of reality TV while the franchise refresh is reportedly undergoing significant changes heading into the next season.

Where remakes have become the norm, especially in the movie industry, Ryan Coogler hit on something unique with his original screenplay, Sinners. In the aftermath, many fans, including myself, are hoping that filmmakers don’t attempt to recreate the energy around Sinners by making the movie in a different font—something that was especially common after the popularity of Jordan Peele’s Get Out.

As a character-driven league, the NBA is propping up new figures; it’ll continue testing new characters. And the hope is that these players will attract more fans, keeping the NBA relevant for generations to come. History tells us there will be new faces—some of whom will cement themselves as the NBA Finals begin tonight. The league depends on it. But any attempt to recreate the magic of past generations will continue to feel bland.

The NBA will never be as cool as it was when I first began watching in the early 2000s. Nostalgia is an impenetrable foe. Plus, it’s hard for anything about this decade to feel cool when we’re only a few years removed from being able to stream MLK speeches on Fortnite.

However, they say lightning often strikes the same place twice, and I know it’s not Thunder, but Gilgeous-Alexander and the Pacers’ Tyrese Haliburton could play their way into bringing that feeling back.

We’re beyond the need for a face of the NBA. The league may disagree, but what we really want—what we’ve always wanted—is good hoops. That has defined our heroes in every era, and I can’t help but think that’s still the case now.

Thank you!

I appreciate you reading! If you enjoyed, please share it with someone special.

Was this forwarded to you? Sign up here to receive my next newsletter directly in your inbox.

Support the newsletter: If you’d like to support my work, consider becoming a Paid subscriber to Feels Like Home or buying me a coffee.

Stay connected: For more content and updates, visit my website or follow me on Instagram, Threads, and LinkedIn.

I think about this all the time, how much less “cool” athletes and celebrities are now that we have so much access to them. There is no mystery left! It’s a different generation, but I think if we didn’t have to watch our favorite players market Taco Bell they might maintain a bit more allure (for me, at least). Isn’t that part of loving a star— being able to fill in what we don’t know about them with our own vision that makes them cool in our minds?

love this, I finished a race, religion, and science fiction class so this may sound like pushback in an unhealthy way, but re: lilo and stitch, I wonder if, beyond capitalism and marketing, who gets to set the boundary of stories that are nostalgic to us? I am very crotchety when it comes to remakes or reboots. heavy. and. as I watch people rage over various reboots and remakes if there isn't some kind of religious fascination with things that are part of our formation/youth? As I think of the Lion King live action (which pisses me off), I wonder if in the remaking of a story, older generations should release our control of the stories so that they can serve new populations? anyway, my nerdy musing (also, this has nothing to do with how much I hate capitalism and the ways that franchises just try to make money off of repackaged shhhhh)