We're All In It

My case against dance circles

At any party, I always look forward to the part of the night where the pleasantries stop and the stank face begins. Where a particular song can bridge the gap between me and those I love, those I haven’t talked to in a while, and those I’ve never met before. I’m talking about the part of the night where everyone’s first language becomes dance. Now here’s the thing: I don’t just dance. I sweat. I yell. I free myself of one shirt button every hour until the room is graced with my chest hairs.

Since I was a kid, my body has been moved by music toward a place of performance—whether I consciously realize I’m performing or not. And while I enjoy a few eyes on me, I’m less comfortable with every eye on me. That’s why I strongly oppose dance circles. You know, when one’s movement begins to catch the attention of a larger group until everyone has formed a loosely shaped border around that person, leaving them to fend for themselves until it’s time for the next person to willingly (or unwillingly) enter the circle and try their hand at impressing the crowd.

While I’m happy to oblige the newly formed audience for a few seconds, eventually I turn to my closest comrades on the dance floor almost as if to say: ‘I’m not here to perform. I’m here to dance with you.’

The best concerts I’ve been to are the shows where the artists see the act of performing as mutual—as something they do with the group in attendance, not merely for them.

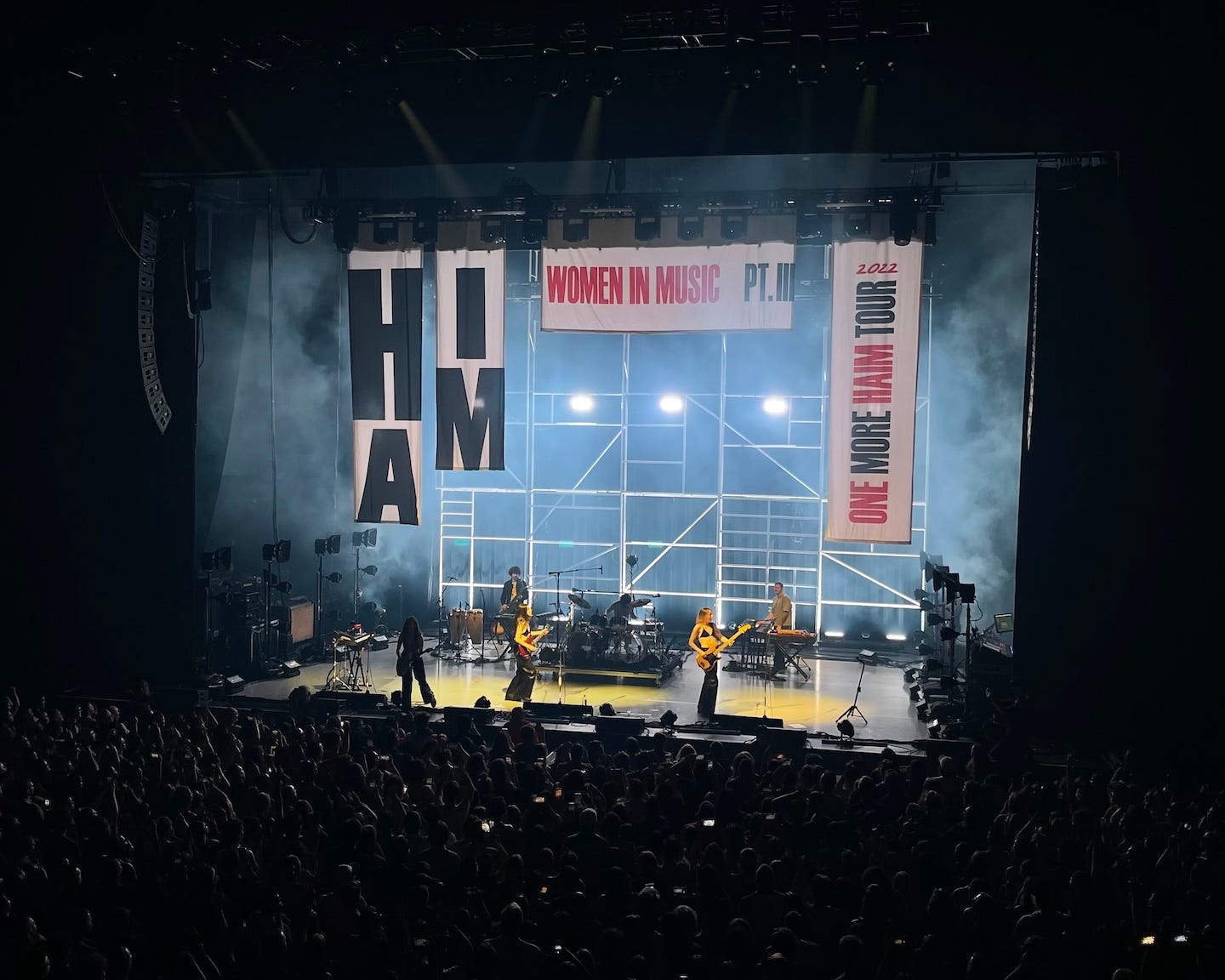

During Memorial Day weekend in 2022, Elizabeth and I traveled two hours to Cincinnati to see Haim in concert. Prior to the show, we had seen a few Instagram posts that showed Haim performing for a sold-out crowd at Madison Square Garden. We vowed that we’d do everything in our power to see them live if they ever came anywhere near our home of Columbus, Ohio.

Due to a COVID outbreak on their tour, Haim ended up postponing their Cincinnati show, which opened the door for me and Elizabeth to go. Although we wrestled with how spontaneous we were willing to be, the show was now scheduled for a Sunday night with both of us having Monday off, making it a no-brainer for us to attend. We decided to make the trip and were both extremely happy we did.

From the moment Haim opened the show with “Now I’m In It,” a bonus track on their 2020 album Women in Music Pt. III, it became clear this wasn’t a show where they expected us to be spectators. They were there to sing and dance with us. In other words, we were all in it. From the balcony front row, I yelled every word to “I Want You Back” and danced my way through “3 AM.” We sang along with Danielle to introduce “Gasoline” and accented the chorus of “The Wire” by all raising our arms in unison when the beat instructed us to.

It felt like all of us were adopted into the Haim family for the night. But that’s what singing and dancing with your people does. It brings us closer, allowing the things that excite us to shine a light toward those who share that same excitement.

When the DJ at Elizabeth and I’s wedding let Kanye’s remix of Chief Keef’s “Don’t Like” roar through the speakers, those of us who knew the song immediately met in a cloud of sweat and flailing arms and screamed every word. It didn’t matter who else was in the room or what they thought about the language in the song. We had each other. And even if this holy moment didn’t come packaged in politeness, we all knew it was our communion table. Let us come, take, and eat.

In recent years, I’ve learned new ways to engage with the language that evangelical Christianity gave me. I’ve gotten the question a few times if I still consider myself a Christian—and while I don’t necessarily identify with the label anymore, I still acknowledge the ways in which Christianity has shaped me and probably always will.

Christianity is my native tongue—and although I’ve learned new languages over the years, it would be insincere for me not to acknowledge the ways Christianity has shaped me. And accepting this is also me recognizing the toxic instructions I’ve been handed by Christians. How people on the margins have had their oppression perpetuated by the words and actions of Christian institutions.

While I don’t necessarily believe evangelical Christianity and its churches can be reformed in a way that liberates oppressed peoples—or that enables a world where we all have everything we need—there is language within Christianity that’s been helpful for me in understanding what it looks like for us to be freed from harmful systems. I think mainly about the Christian understanding of “home.” This idea that we are loved and accepted as we are and can always return to this reality no matter where it’s found. And when we come home, we’re met with open arms and celebration.

A few years back, I was reminded that my cousin and I used to try destroying each other when we were growing up. We would impersonate our favorite wrestling moves on one another in my grandma’s basement, which always led to an influx of emotions. Two boys understanding how to relate through domination. But when we celebrated my little brother’s high school graduation, me and my cousin found ourselves in each other’s arms, swaying side-to-side to “Swag Surfin’” — a song that requires togetherness.

I guess that’s what happens when you come home—you live with the good, the bad, and the uncomfortable, finding and holding space to move as one. Not a performance for one another, but dancing with each other. Because we can only watch each other for so long until we all must jump in the middle and keep us alive.

Thank you!

I appreciate you reading! If you enjoyed, please share it with someone special.

Was this forwarded to you? Sign up here to receive my next newsletter directly in your inbox.

Support the newsletter: If you’d like to support my work, consider becoming a Paid subscriber to Feels Like Home or buying me a coffee.

Stay connected: For more content and updates, visit my website or follow me on Instagram, Threads, and LinkedIn.

Bro! This reflection on dance circles is genius! And then weaving in evangelicalism 🤯👏🏽